The invention of the telephone is credited to American Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson in the mid-to-late 19th Century. Although Bell ultimately prevailed in the early signs of patent wars to come in the tech industry, there are a number of inventors who helped contributed technological and conceptual advancements that furthered telephone technology in this same timeframe. By the end of the 19th Century, the telephone would find commercial success and has significantly evolved over the past century +.

Early Telephone Pioneers

There are number of early telephone pioneers who helped contribute technological advances to the field which culminated in Bell and Watson’s invention of the telephone in the later portion of the 1800s. The inventors ranged the globe; however, Bell proved to be the first to be able to combine technical and business prowess which resulted in the invention we all know as the telephone today!

Charles Grafton Page

Charles Grafton Page, 1812-1868, lived in America and at the age of 25 was able to send electric current through a coil of wire that was set in between the two poles of a horseshoe magnet. During the test, Page, made the observation of the connecting and disconnecting of the current causing an audible ringing sound in the magnet. He is credited with calling this effect, “galvanic music.”

Innocenzo Manzetti

Innocenzo Manzetti is credited with first considering the idea of what is known as a telephone today in 1844. Many Italians actually consider him to be the inventor of the telephone since he is purported to have provided his automaton the “power of speech” in 1864. Manzetti did not patent his invention, but it was reported in the press in Paris at the time in the Le Petit Journal. There were allegations of potential intellectual property theft against Alexander Graham Bell; however, there are no substantiated records which would indicate his invention borrowed from Manzetti’s work.

Charles Bourseul

Charles Bourseul, a French telegrapher, published a plan for conveying sounds and speech via electricity in the magazine, L’Illustration, in 1854. He also published his ideas in Didaskalia on September 28th, 1854. His description included “Make-or-break” signaling that was capable of transmitting tones and vowels, but did not follow the analog shape of the sound wave. As a result, the technique was not able to transmit complex sounds or consonants.

Johann Philipp Reis

Johann Philipp Reis was the first inventor to produce an electromagnetic device that could transmit indistinct speech, musical notes, and occasionally distinct speech in 1860 by using electric signals. He was also the first person to introduce the word “telethon” for his invention. The first phrase spoken on Reis’s device was, “Das Pferd frisst keinen Gurkensalat,” or “the horse doesn’t eat cucumber salad” translated to English.

In Reis’s device, there was a diaphragm that was attached to a needle that was subsequently pressed to touch a metal contact. The design resembled that of Bourseul; however, Reis used the term “molecular motion” to describe the points of contact of his transmitter. The device was considered challenging to operate due to the relative position of the needle and contact being crucial to the proper operation. Although the invention can be referred to as a “telephone,” it was not a commercially practical phone since it was not able to provide a solid transmission or copy of any sound supplied to the device.

Before 1947, Reis’s invention would be tested by Standard Telephones and Cables (STC) in the U.K. Their results found that it could transmit and receive speech; albeit very faintly. During this timeframe, STC was in the middle of bidding for a contract with Bell’s company, American Telephone and Telegraph Company, and did not publish their results to help maintain Bell’s reputation as the inventor of the telephone.

Antonio Meucci

Another early telephone pioneer was Antonio Meucci. He is credited with creating a voice communicating device in 1854 and called it the telettrofono. He would later file a caveat at the U.S. Patent Officer in 1871 which describes his invention; however, he did not mention a number of details required for an operable phone to include the electromagnet, diaphragm, conversion of sound into electrical waves and vice versa, or other essential features of an electromagnetic phone.

Meucci first demonstrated his invention in the United States at Staten Island, New York in 1854. He claimed to have invented the paired electromagnetic transmitter and receiver that used the motion of a diaphragm to modulate a signal in a coil through the movement of an electromagnet; however, the information was not included in his patent caveat. Another discrepancy found in Meucci’s 1871 patent caveat was that it only used a single conduction wire with the transmitter/receivers being insulated from the ground return path.

During the subsequent decade, Meucci was successfully credited with inventing the ability to inductively load telephone wires to increase long-distance signals. Due to his poor English skills, lack of business capability, and burns suffered from an accident, he was unable to see commercial success from his work.

In 2002, the United States House of Representative recognized Meucci for his early work on the invention of the telephone. The Congressional resolution did state, that if Meucci had been able to pay the $10 fee for maintaining his patent caveat after 1874 that Alexander Graham Bell would not have been able to obtain a patent in March of 1876. Instead, Meucci would have been provided a chance to prove to the patent examiner that the device he described was the same as what Bell proposed. As a result, the resolution did not provide credit to Meucci, but merely stated he would have had his day to go head-to-head with Bell at the time to prove his invention was the original telephone.

Poul la Cour

Poul la Cour was a Danish inventor who in 1874 conducted experiments with various audio-enabled telegraphs on a telegraph line run between Copenhagen and Fredericia. In the testing, he used a vibrating tuning fork to help interpret the line current. After the current passed through the length of the telegraph line it would resonate at the same pitch on a tuning fork located at the opposite end. Additionally, he was able to record the hums on paper by making the electromagnet receiver act as a relay that would then turn on a Morse code printer through the use of battery. La Cour would make no claims for being able to transmit the human voice with his invention—only pure tones.

Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray from Highland Park, Illinois is credited with developing a tone telegraph in the same timeframe as La Cour’s invention. In Gray’s device, he used a number of vibrating steel reeds that were tuned to various frequencies to interrupt the current. At the opposite end of the line, the current would pass through electromagnets and vibrate similarly tuned steel reeds located near the electromagnet poles. The “harmonic telegraph” invention of Gray was subsequently used by the Western Union Telegraph Company. This allowed the company to transmit more than one message at a time over a telegraph line due to the harmonic telegraph technology proving to be an early multiplexer. Gray would subsequently obtain U.S. patent 166,096 for his invention of the “Harmonic Telegraph.”

On February 14th, 1876, Elisha Gray’s lawyer would file a patent caveat for a telephone on the same day that Alexander Graham Bell’s would. Gray’s patent caveat application described a water transmitter very similar to the experimental transmitter that had been tested by Bell. The similarities raised questions about which inventor was “inspired” by the other.

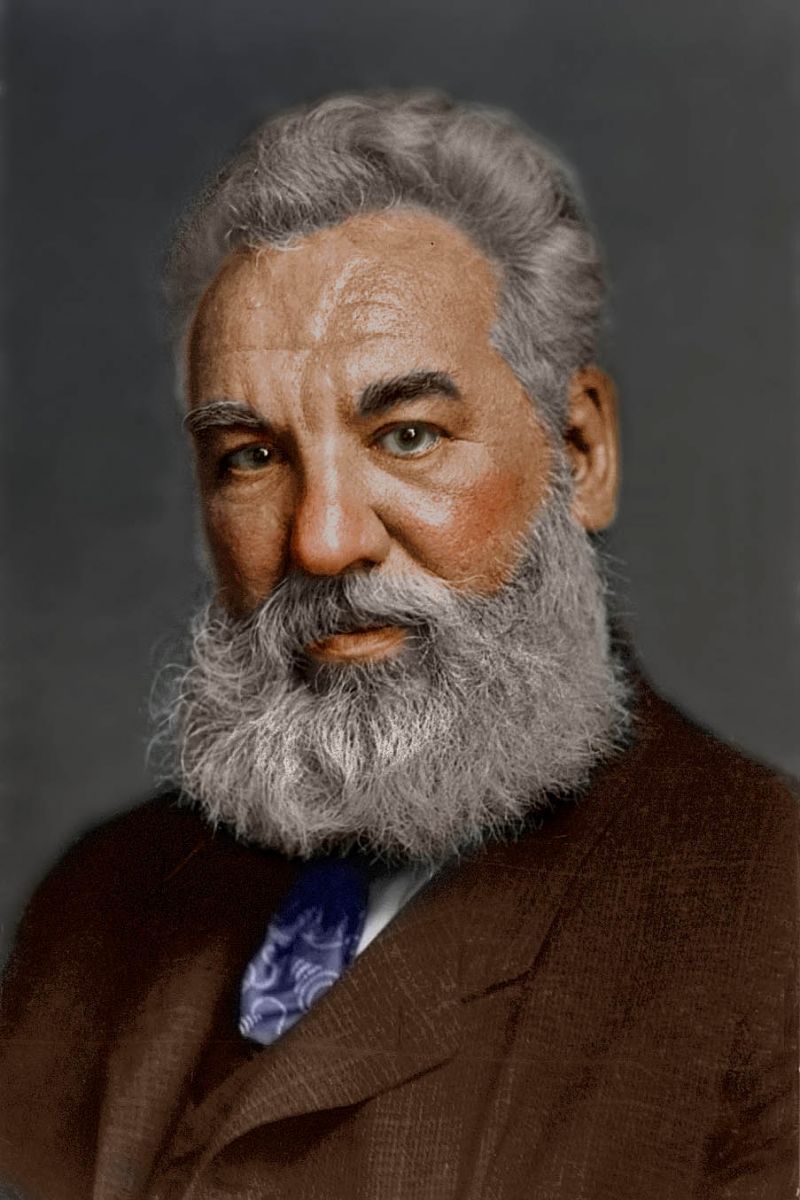

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell continues to be famous well after his death for being the inventor of the first usable or practical telephone. He was the first inventor to obtain a patent in 1876 for a device that was able to transmit voice and other sound “telegraphically” after he conducted numerous experiment using a variety of transmitters and receivers. Unlike other scientists in his day, Bell was an accomplishment business man who had a number of wealthy and well-connected friends to help him take the telephone to commercial success in the years after the invention.

While Bell was teaching vocal physiology at Boston University, he spent a significant amount of time training other teachers in how to teach deaf mutes how to speak. At the same time, Bell also conducted a number of experiments with Leon Scott in recording the various vibrations of speech using a phonautograph. This initial device, consisted primarily of a thin membrane that would be vibrated by the voice. It carried a light-weight stylus that would then trace a line on a plate of smoked glass to represent the waves of sound in the air. This research provided Alexander Graham Bell with the necessary background in electricity and sound waves to continue his own experiments.

A few years later in 1873-1874, Bell conducted subsequent research work using a harmonic telegraph following the examples of Reis, Grey, and Bourseul. He would use designs that were based on on/off/on/off make/break current interrupters that were driven by vibrating steel reeds. These reeds would then send interrupted current to a remotely located receiver electro-magnet. This magnet would then make a tuning fork or steel reed vibrate.

On June 2nd, 1875, Bell and his assistant, Thomas Watson were conducting an experiment when one of the receiver reeds failed to respond to the current being supplied by an electric battery. Bell would then tell Watson to pluck the reed that failed to work thinking it had gotten stuck to the magnet’s pole. Mr. Watson did so, and Bell would hear a reed at his end of the test line vibrate and transmit the same tone without an interrupted on/off/on/off current from the transmitter to make it vibrate.

After conducing subsequent experiments, Bell was able to prove that his receiver reed was set into vibration through the magneto-electric current induced in the line by the motion of the distance receiver reed located near its own magnet. He found that the battery current was no responsible for creating the vibration, but was required to supply the magnetic field that the reeds required to vibrate. Bell then hypothesized that since he never broke the circuit of the line, the complex vibrations of human speech could be converted into modulated current. This would then be able to reproduce human speech at a distance.

Once Bell and Watson made their discovery on June 2nd, 1875, Bell then reasoned that a skin diaphragm could better reproduce sounds similar to the human ear when connected to a hinged armature or steel or iron reed. Just one month later, on July 1st, 1875, he had Watson build a new receiver that included a diaphragm of goldbeater’s skin that used an armature of magnetized iron attached to the middle. It was allowed to vibrate in front of the pole of an electromagnet that was in circuit with the line. A second membrane was then constructed as a transmitter and was referred to as the “Gallows” phone. Several days later, the devices were tried together with one at each end of a line run between a room in Bell’s house and the basement. Bell would speak into the transmitter and state, “Do you understand what I say?” Mr. Watson required with a “Yes.” The voice sounds were not distinct; however, and the armature of this device would tend to stick to the electromagnet pole and rip the membrane. Work on the telephone invention would then stall due to Bell falling sick until his U.S. patent 174,465 was approved.

Alexander Graham Bell’s Successful Telephone Test

The first bi-directional transmission of distinct or clear speech by the inventors was made on March 10th, 1876. Bell is credited with stating, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you.” Watson of course replied. Bell would test Gray’s liquid transmitter design, but only after he had his patent granted. Since he did not consider the liquid transmitter to be practical, Bell would focus on further improving the electromagnetic telephone after March 1876.

Bell’s original telephone invention would undergo rapid improvement. The original double electromagnet would be replaced by a single permanently magnetized bar magnet that only had a small bobbin of fine wire surrounding one pole. In front of the pole, there was a small disc of iron that was fixed in a mouthpiece which was circular. The disc would act as both an armature and diaphragm. The new design was subsequently patented by Bell on January 30th, 1877. Bell was also credited with making the first long distance telephone call on August 10th, 1876 from Brantford, Ontario to Paris, Ontario which was a distance of 10 miles or 16 kilometers.

Commercializing the Telephone

Although there were a number of inventors who conceptualized the telephone or made similar discoveries, Bell is equally famous for being able to develop telephones that were commercially practical. As a result, Bell was able to build and grow a successful business around the telephone, adapted telephone exchanges and switch boards, and made a number of additional improvements to telephony with his engineers.

Follow Us!